Mowing the Grass

One of the main tasks on the finca, year after year, is mowing the grass. Winters are wet and windy, often cold, going down to a degree or two below freezing, albeit not for long, for no more than a few nights, warming up over the mark during the day. It is the sort of cold that gets into the bones however. One can see it in the elderly of the village, many of them illustrative of the Sphinx’s riddle, walking on three legs in the evening of their lives. Central heating in the houses is not all that common since the coldest part of the winter often lasts only from mid-December through mid-February. Wood burning stoves or gas heaters keep the chill off.

Planting time is from the end of February all the way through March and by April things have warmed up considerably, often with April showers.

Which brings us to May flowers. By mid-May the countryside is resplendent with the reds, whites, yellows and purples of spring – poppies, peonies, cistus, wild iris, gladioli, giant fennel are in the caminos as well as the buttercups and daisies that carpet the olive groves. And chamomile. Grasses by this time, untended, have reached almost waist height. Quaking grass, hare’s tail, wild oats and barley, and others named only in Latin, all are in full upright, waving splendor, nodding and bowing in the wind, sometimes flattened only to perk up again.

As May folds into June, the sun now high in the sky and blazing, so the grasses and flowers dry out, crispen, becoming within the space of a week or two, less the refulgent cloak of spring, more the threatening tinder of summer fire. It is in this short space of time as the lush green foliage dries out into brittle stalk that it becomes possible to cut through the drying undergrowth and terminate this lustrous landscape before it threatens.

The choices for cutting the straw and dry grass are these: a donkey to graze the land; a desbrozadora; a sickle; a scythe; and poison.

Most of our neighbors favor the last of these. An olive grove, a vineyard, a fig plantation, is only considered well managed if the suelo, the floor, is as clean as a billiard table. In early spring the farmers are out with back-mounted sprayers applying herbicide liberally. Monsanto’s Roundup containing glyphosate is the product most commonly used and although there is strong evidence that it is carcinogenic, that it causes severe eye problems and is toxic to aquatic life the European Food Safety Authority and the European Chemical Agency have recently reauthorized its use.

A poisoned landscape

Our policy not to use chemicals on the land, and our reasoning, are met with skeptical shrugs often followed by warnings about fire. We hastily reassure whoever it is we are talking to – Antonio, Juan Antonio, Andres and others – that we take that seriously so we have resort to the other technologies for keeping the grass under control.

Firstly, the donkey, on loan to us from our neighbor Andres. Wairimu as we have called ‘our’ burra, will happily graze one-and-a-half to two kilos of hay a day, so the one hectare of grazeable pasture is fine for spring and summer. We have to restrict her activities to the back parcels however since she has an appetite for the fruit and nut trees that we have growing in front of the house. She will not eat brambles or any of the other woody bushes that proliferate. Those we take care of with clippers. Now, as I am writing this at the beginning of September, she has eaten almost all the grass so we are supplementing her diet with lettuce and other kitchen scraps plus dried figs and generous portions of hay, broken out of the bale as a sort of donkey weetabix. She will be going back down to lower pastures towards the end of the month when we are no longer around to keep her company.

Wairimu the donkey, at work.

The desbrozadora, a shoulder mounted handheld two-stroke weed-whacker, will deliver a neat haircut to a clear stretch of dry grass. If the grass is at all green or wet or there is robust weed growth then the little two-stroke finds it hard going and chokes. We have managed to destroy two Chinese-made machines by pushing them too hard in this way. Now we have a proper Swedish machine, less wimpy, less temperamental. Apart from having to be careful not to overload the machine the other disadvantages are the horrible noise and the pollution of the two-stroke. Compared to glyphosate, these are lesser evils. I do worry sometimes about the toll the vibrations take on my nervous system. At the end of a long session one’s hands can be all a-buzz for half an hour after.

The desbrozadora, at work.

The scythe and the sickle are almost as old as agrarian humanity itself. The sickle that one can buy in an agricultural hardware store today is not at all unlike that handheld cutter used by farmers in Mesopotamia as much as 10,000 years ago. Nor is the western model unlike the instruments indigenous to China, India and South America, a testament to the universality of ergonomic design, a careful extension of human arm, wrist and hand. The shape itself is iconic. Sometimes called a billhook, the shape of an avian beak, and the sickle moon, the first phase of a crescent, a slender ‘C’. More powerful perhaps is the metaphorical content of the shape, representing centuries of peasant disgruntlement with their overlords encapsulated by the sickle that is both livelihood and armament. Histories of graphics, mostly so cravenly referent to Madison Avenue, if they attend to the matter at all, tend to underestimate the semiotic power of the hammer and sickle and its historical associations.

The sickle: from Old English, sickle;Latin secula; secare = to cut.

The sickle is good for cutting around trees and stones, surgically removing grasses and especially brambles from their covetous embrace of those plants we want to survive and prosper - the older ones - figs, vines and olives – as well as the younger, saplings of pomegranate, almond, hazel, bay laurel and cork oak. But for the wider field, the sickle is backbreaking work. In many parts of Africa one sees peasant women, bent double in a yogic crease at the hips, working with a sickle for harvesting. Van Gogh’s Reaper with Sickle shows just how contrary to our biped design that appears to be. Nancy works in that tradition, swiping away at the grasses and brambles as well as the slender shoots of broom and cistus. Her back is stronger than mine.

Backbreaking work.

The scythe has the great advantage of not requiring the user to bend double and is thus more ergonomically sustainable for wide swaths and long days. Not as old as the sickle, its archetype stretches back a mere 2,000 years or so and has evolved only in detail, not in basic concept.

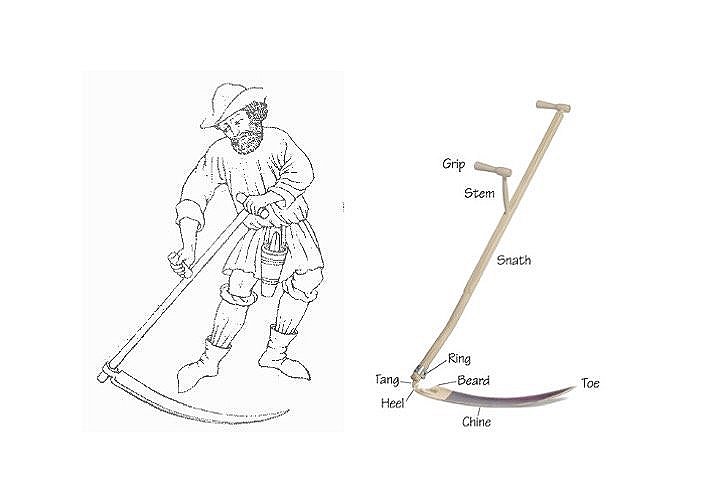

An ancient tool described in short, old words.

The model I use is the Bellotta 2509-22, purchased at the Casa Mayor agricultural hardware store in Merida. This modern scythe has an aluminum snath and a steel chine measuring 500mm from beard to toe. The naming of the parts is a reminder of its ancient lineage. Short, old words.

The Bellotta 2509-22.

It weighs only 500 grams, no more than a small packet of flour, much less than its pre-industrial forebears. Unlike those earlier models the handles – the ‘grips’ – are in a fixed position so not amenable to bespoke fitting to its user, more measured to the average man, a full grown peasant of 1,75m. – and, as it happens, me. This tool is a model of ergonomic design. The left grip at the top is the fulcrum for the movement of the scythe while the lower grip, powered by the right hand and arm, the main lever force. The blade (or chine) is curved like a scimitar reflecting the radial motion of cutting and it is set at an angle to bring the cutting edge horizontal to the base of the stalks. A particularly cunning detail is the upturned rim of the trailing edge of the blade allowing one to sharpen the blade at a constant angle.

The trailing edge is upturned to allow the sharpening stone to hone a consistent sharp angle on the leading edge.

There is a famous passage in Anna Karenina of Levin, the urban intellectual, learning the simplicity of the peasant life, joining the workers in scything the corn. Tolstoy describes Levin’s struggle (actually Tolstoy’s own) learning how to use this simple, ancient tool, fighting with it and ending the day exhausted. This in contrast to the old peasants who allow the natural swing of their arm to set a metronomic pace that is graceful and efficient, leaving them tired at the end of the day – but not exhausted.

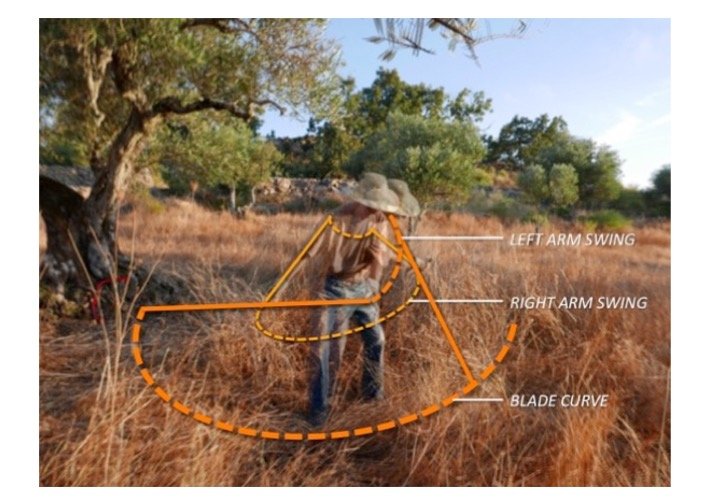

This passage was in my mind as I watched Agustin, our neighbor who tends a finca down the hill, make a short demonstration. Effortless, even in the hot sun he hardly broke a sweat. As I tried it out later – by myself so as not to invite ridicule – I eventually understood that the secret is in the swing, in allowing the scythe to rotate around the upper grip, using its own weight, pendulum-like, to provide the momentum behind the cut. The right hand is just a guide. Don’t force the blade, allow it to fall, I kept telling myself until finally I heeded my own advice.

The natural flow of a scythe

I am still more Levin than peasant it has to be said, nevertheless pleased with having cleaned out our front field and parts of the olive grove without inflicting any permanent damage on myself. And still in awe of this ancient design and wondering if an iPhone could ever sustain such longevity.

HM 1st September 2017