CENTRAL ARTERY / TUNNEL PROJECT, BOSTON 1989-97

The Central Artery Tunnel project was conceived in the Boston Transportation Planning Review of 1972. Detailed planning began in 1982, construction started in 1991 and the project was completed in 2004. A joint venture of Bechtel and Parsons Brinckerhoff was responsible for engineering and construction management. Wallace Floyd Associates was the lead sub-consultant responsible for planning, urban design, architecture and landscape architecture. Wallace Floyd was joined by Stull and Lee (for urban design and architecture) and Carol R. Johnson (for landscape architecture). From 1989 to1997 I was employed by Wallace Floyd as Chief Architect on the project and later as our firm's principal-in-charge.

The main idea was to remove the congested elevated highway (I-93) that separated the city from its waterfront and replace it with a tunnel that would also have greater capacity. In addition, the project would extend the Massachusetts Turnpike (I-90) from its current termination in Chinatown, connect to the hitherto undeveloped wasteland of the South Boston seaport, continuing under the harbor to Logan Airport in East Boston. The project consisted of 7.8 miles of highway consisting of viaducts and tunnels, ventilation buildings, an operations control center and numerous emergency vehicle stations and a central maintenance building.

The design and construction process was in three phases. Our team was responsible for Preliminary Design, establishing program, siting, architectural massing and establishing standard details and specifications throughout the project. Final Design was distributed to companies who, following the preliminary design, standard details and specifications, became the engineers or architects of record. In the construction phase, responsibility came back to the construction management team (including the architects) for site administration. At its peak there were about 1,000 people employed on the design and construction management teams. The core team of architects, planners, urban designers and landscape architects amounted to about 45 people.

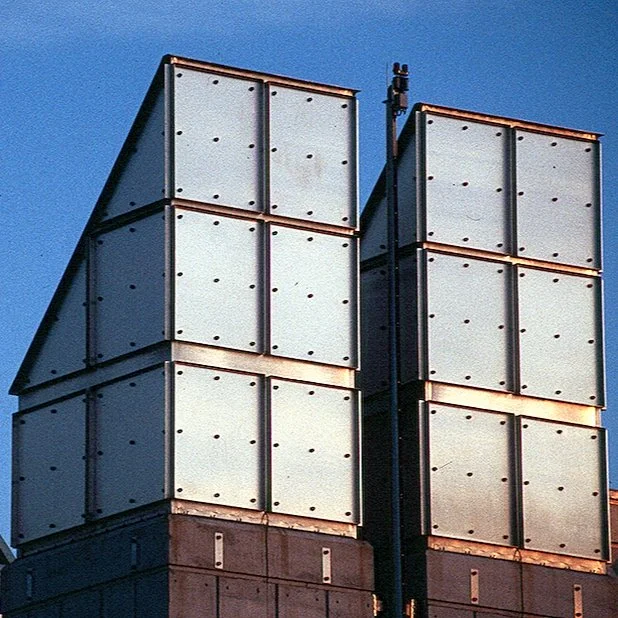

Ventilation Buildings

The function of the ventilation buildings is simply to funnel fresh air into the tunnels and to exhaust stale air out to the atmosphere. These were very large buildings to be inserted into the urban fabric and they had no resident workers. The architectural challenge was therefore to fit the building into its immediately surrounding context, to create an architecture that would mutely explain their function, and at the same time establish a family relationship so that they could be recognised for what they were in diverse locations throughout central Boston. A major technical innovation was achieved by adopting rainscreen panels as the primary cladding method.

Boston Central Artery / Tunnel; Project: I-90 / I-93 alignment

Boston Central Artery / Tunnel Project: design team. Painting by Gail Boyajian, architect and team member. Her implicit reference to Gericault’s The Raft of the Medusa reflects some moments of the lived experience on this project. Tatlin’s Tower evokes the constructive dialectic between life in the cubicles and the raging natural force of the Trevi Fountain (referred to in one of the original design concept papers).

Ventilation Building #1 Fort Point Channel (Ondras Associates)

Ventilation Building #3, Atlantic Wharf (Leers Weinzapfel Associates)

Ventilation Building #4, Haymarket (Arrowstreet)

Ventilation Building #5, Congress Street (Wallace Floyd Associates)

Ventilation Building #6, Boston Martine Industrial Port (Barrientos)

Ventilation Building #7, Bird Island Flats (TAMS)

Ancillary buildings

The family of buildings was designed to include the Operations Control Center (housing computers that controlled the traffic system within Route 128); the Emergency Stations housing police and ambulance vehicles; the Vehicle Maintenance workshops; a ferry terminal and numerous headhouses.

Operations Control Center, South Boston (ADD Inc.)

Emergency Response Station, South Boston (ADD Inc.)

Maintenance Building and fuelling facilities, South Boston (Wallace Floyd Associates)

Jeffries Wharf Ferry Terminal - now demolished (Wallace Floyd Associates)

Viaducts and Tunnels | coordinating details

The main architectural aim in highway design is to create visual continuity from the driver's point of view. In the case of the viaducts they must also have a simple elegance within the framework of the city. Considerable attention was paid to the formwork rustication on piers and retaining walls to mitigate weathering and to lend scale to these massive elements within the urban context. The chief challenge of the tunnels was to give the driver a sense of place and direction. Numerous and repetitive attempts were made to incorporate art into the wall finishes of the tunnels but in all cases proposed designs were rebuffed by the Federal Highway Administration. Signage and lighting were also a major design element in the architectural repertoire.

A conceptual matrix coordinating form, texture and colour throughout the project

Standard details for the vent stacks and air intake louvers in VB7, VB5 and VB6 (L to R)

Landscape emphasises a specificity of place throughout the project. The Zakim bridge in the background was designed by Professor Christian Menn with architectural coordination by Wallace Floyd.

Piers, viaducts, boat walls and tunnel portals are rusticated in the formwork to give scale and proportion to concrete surfaces and to control natural weathering.

The Architecture / Landscape Architecture / Urban Design Team - Summer Street Bridge 1991

Wallace Floyd Associates | Stull & Lee Inc. | The Primary Group | Carol R Johnson Associates