The Cavell Street Mezuzahs

Cavell Street, Ford Square, Whitechapel

In 1984, as a young-ish architect, I was working in London for the firm Levitt Bernstein Associates. We had a contract with the Bethnal Green and East London Housing Association to do a ‘gut rehab’ on seven houses in Cavell Street forming one side of Ford Square in Whitechapel. The old London Hospital was close by, where my maternal grandmother, one of the first women doctors in England, had run a maternity clinic.

The houses, as dilapidated as they were, had until recently been inhabited mainly by the descendants of Jewish immigrants from Russia and Eastern Europe in the 1890’s and early 1900’s, successors to many lines of immigrants who made Whitechapel their first home in their flight from persecution.

On first appearance from the street, these three-storey row houses, as modest as they were, looked as if they had been built in the Regency period, at the end of, and just after, the Napoleonic Wars. Fluting on the front door pilasters, the arched windows and the sensitive proportioning of the facade suggested a level of design quality belied by the external circumstances. But the Blitz had taken its toll. The elderly Jewish newsagent who ran the newspaper shop at the end of the row took me down the whole street pointing out where bombs had fallen, when they had fallen including the date and time of day, and where the brickwork had been patched up.

Blocked up entrance door, 1984

Now the buildings were in such a state that we determined the entire back wall, all along the row, had to come down which required the building of new foundations. Under the old brick ‘spread footings’ however, we found coins dated 1795 i.e. a few years prior to the wars and the later emergence of the Regency style. What was the key to this cognitive dissonance? According to Bill Fishman, local historian, a plausible explanation seemed to be that the building may have started before the war but then every able bodied man was called up to fight Bonaparte and it was not until after the Battle of Waterloo that labourers could get back to resume the work – by which time small details and even materials had changed.

Incidentally it was during this time that a television show on building preservation and restoration approached us to feature the project, not as a paragon of fine design but as a counterpoint to those who claim that things were built much better in the old days. To illustrate the point, I was asked to perform in front of the camera a sort of party trick of crushing a brick with one hand. Flaky brick, not superhuman grip, was the message.

In other parts of the demolition we had to remove old fireplaces. As this was going on a powder blue Rolls Royce pulled up on the street, a man of tremendous girth and a disposition best described as forthcoming rolled out of his roller and asked what I would take for the fireplaces, pulling out of his bulging trouser pocket a thick wad of £50 notes to illustrate his earnest. I apologized but said I couldn’t sell them as they were the property of the owner, the housing association. With a bit of “come on, ‘oos to know?” he gave up. His empathy for this ingénue was demonstrated with a patronizing pat on the shoulder and a smile that said quite plainly “some muvvers ‘ave ‘em”. Off he rolled in his roller.

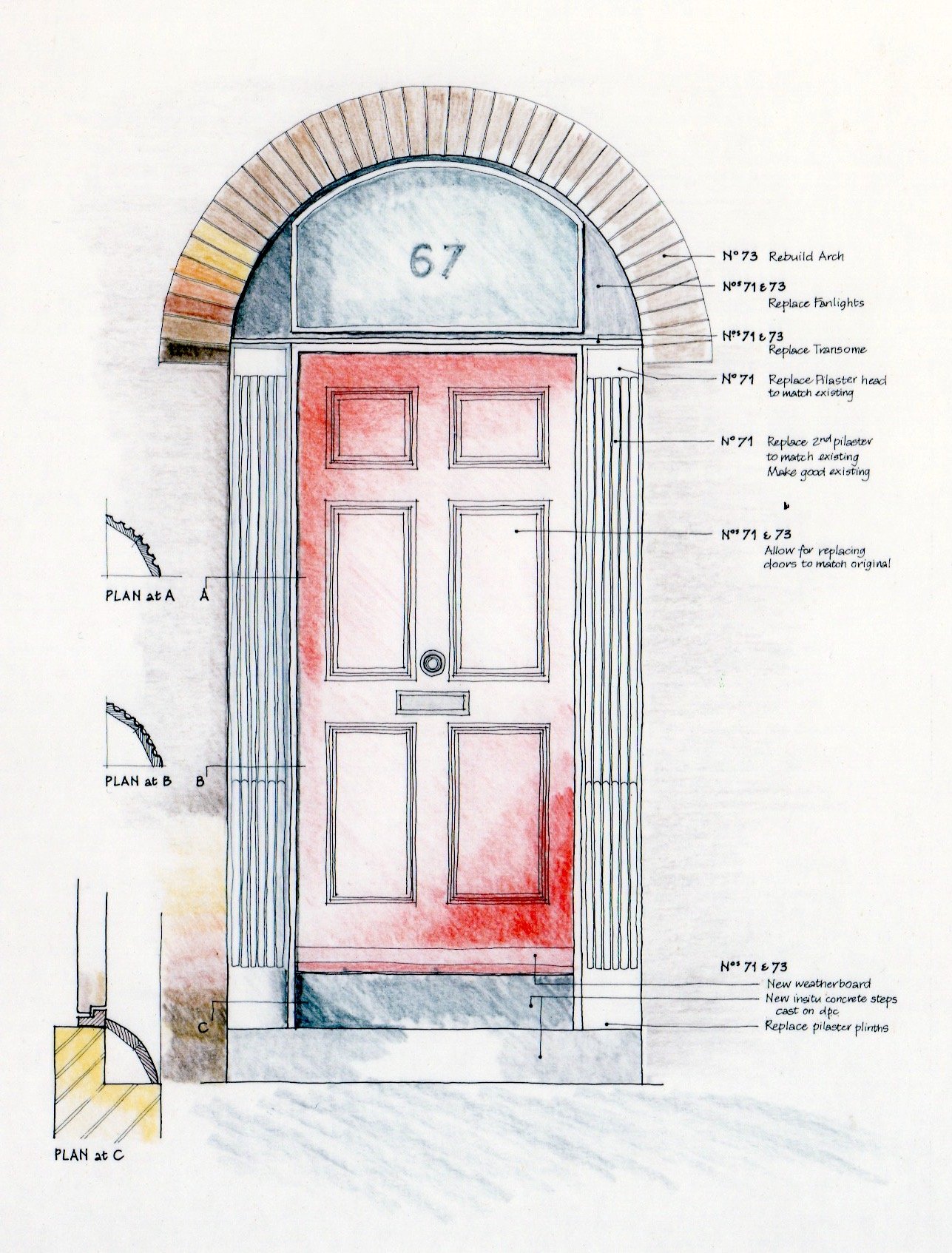

Entrance door renovation: application for historic preservation grant, 1984

More to the point however, and this is where I did take matters into my own hands without consulting the owner, I asked Bill Kennedy the foreman to remove the mezuzahs from the front door posts of each of the houses. My first instinct was to save these small pieces of parchment with devotional observances from the profanity of the dump. I kept them in my desk in the office for a few months until it became time to reconstruct the building. With a special grant we managed to afford crafting a tiny lobby, an ante-room between street and living room, a social insulation between public and private. It was then that I thought it might be a good idea to hide a mezuzah within the stud wall we were creating at the entrance, this unbeliever thinking it only respectful to extend G*d’s benevolence to whoever might be the next resident.

The building was finished in 1985. The next occupants, as it happened, were refugees from Bangladesh, the latest generation in the East London immigration heritage. A few months after the new residents, observant Muslims, moved in there was a firebomb attack on the houses. Ultra-right anti-immigration activists had placed flaming rags through the letter boxes of the front doors. If there had not been a second door on this small antechamber, the fire would have taken hold in the living rooms. The internal doors saved the building and the residents from serious harm. Or was it the mezuzahs?

Cavell Street, 2022

4th May 2025